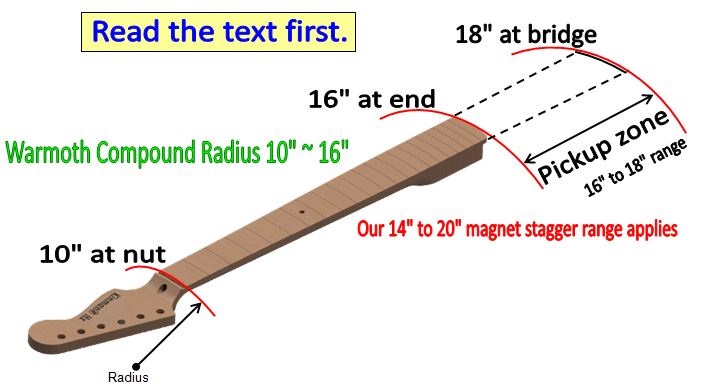

It must be understood that the radius formed by the strings on a Compound Radius fretboard continues to flatten towards the bridge. We call this the projected radii.

As you can see in the upper illustration above, a Warmoth 10″ radius at the nut and 16″ radius at the end of the neck projects to a 18″ radius at the bridge. The section between the end of the neck and the bridge is called the pickup zone and the radius range there varies between 16″ and 20″. The radius range of our Flat magnet stagger is 14″ to 18″ and that covers every different radius between 16″ and 20″ that can be found in the pickup zone. As far as we know Kinman is the only pickup maker to make a custom magnet stagger that suits the 16″ to 18″ range. Click for a complete understanding of Magnet Staggers.

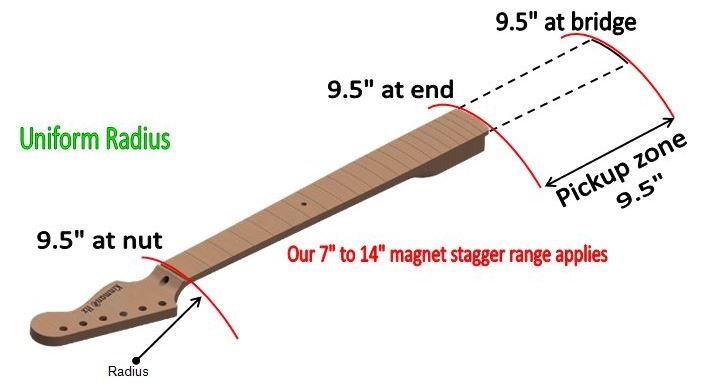

The lower image above is an example of a typical uniform radius fretboard (some being … vintage Fender 7-1/4″; modern Fender 9-1/2″, Gibson 11″; various other brands are probably different).

For the mathematicians among us here is our formula for calculating the projected radius at the bridge.

In the following calculations ∴ = therefore and 100, 144 and 200 are Constants, algebraically denoted as á½ . To begin calculating your projected radius substitute difference between nut and end of neck (6″) for Warmoths most popular compound radii.

EG Warmoth 10 ~ 16″ is 16″ (at end of fretboard) – 10″ (at nut) = 6″ (I.E. difference b/w nut and end of neck)

- On a 22 fret neck, if 12th fret is 100á½ from nut then the 22nd fret is 144á½ from nut

- ∴ 6″ / 144á½ = 0.04166″ which is the radius increment per 1 x á½

- To test this formula 0.04166 x 144á½ = 6.0″ + 10″ = 16″ at 22nd fret, proves it’s correct

- ∴ 0.04166 x 200á½ = 8.33″ + 10″ = 18.33″ Rad at bridge

If you have an order with us and are unable to calculate your projected fretboard radius click “I don’t know” in the Additional Questions and message us with the radius at the nut and end of the neck and we will work out the best solution for you.

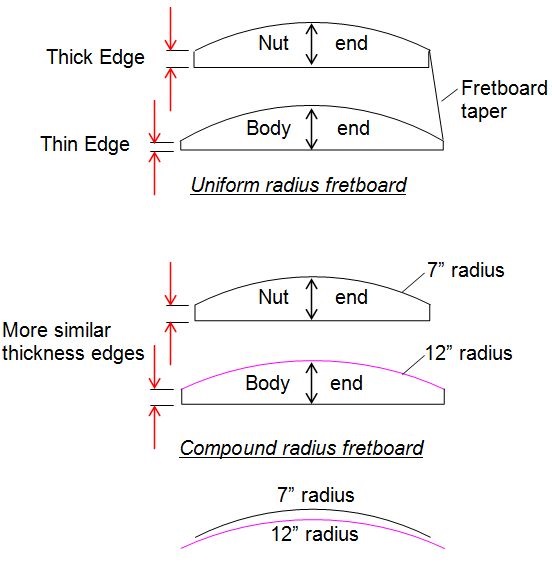

By the way, have you noticed the fretboard is thicker at the Nut end than the body end of most other guitars aside from Fenders which have a veneer fretboard? The illustrations below show the reason. And gives rise to the suspicion that Leo Fender understood geometry and cared about the appearance of his guitars and went to extraordinary lengths to avoid the unsightly increase in freetboard thickness at the nut end. Chris Kinman was also as fussy as Leo and Kinman guitars manufactured from 1984 onwards had slab fretboards that were compensated so the edge was same thickness at the Nut and the body end. We achieved this by making the fretboard thicker at the body end. The different geometry had the collaterial benefit of introducing a slight but significant neck-to-body pitch thereby increasing string heights over the pickup zone.

Slab fretboards: An unforeseen benefit with compound radii when applied to a slab fretboard (as distinct from a veneer fretboard or a full Maple neck with integrated fretboard) is that the edge of the fretboard is not as disproportionately thicker at the Nut end than it is at the body end compared to a uniform radius. The illustration below shows why a uniform radius presents a thicker edge at the nut end.